Strange garden

Although not as fully realised as the Wild Swans’ The Coldest Winter for a Hundred Years – one of my favourite albums of the 21st century – Death Must Be Beautiful, a resurrected solo work from 2004, sees Paul Simpson in equally strong songwriting form. Emerging out of a depression following the death of his father, lyrically it’s bleaker than The Coldest Winter, with references to whirlpools, decomposition, syringes, and poison, and that’s just from the titles on side one of the LP.

The gloom and doom is leavened by Paul’s habitually buoyant melodies and a predominantly acoustic musical prettiness. The players include Wild Swan Ged Quinn on piano and the Granite Shore’s Nick Halliwell on guitar, and it’s produced with a gossamer-light touch by another legend of the Liverpool music scene, Henry Priestman (songwriter and former member of Yachts, It’s Immaterial, and the Christians).

While two or three of the 14 songs are a little on the slight side, even these more fragmentary ones are never less than engaging. Paul’s songs often tend to look back with a kind of nostalgia that finds grim solace in how hard things were back then, noting as they go the beauty in austerity, and these are no exception. Extreme situations force heightened feelings and responses. Wounds either linger without healing, or are opened up to be re-examined as if they had never mended in the first place.

There’s no conclusive rallying cry here, nothing which suggests resolution or a path out of depression, save the music and the process of creation itself. Death Must Be Beautiful catches Paul progressing towards The Coldest Winter…, and its songs (which include a version of Disintegrating with the melancholia heaped higher than on the Tracks in Snow version) both presage and come close to matching the perfection that the Wild Swans achieved on that album.

The LP is pressed in suitably funereal green vinyl. Signed copies of Paul’s artwork for the LP are available as a separate print, with his cheerfully bleak notes about the songs on its flipside. All in all, it’s a beautiful living thing.

The Edge of the Object ebook now available!

Please click here to buy a copy of the ebook of my novel, The Edge of the Object, for a special launch price of £3 (£5 subsequently).

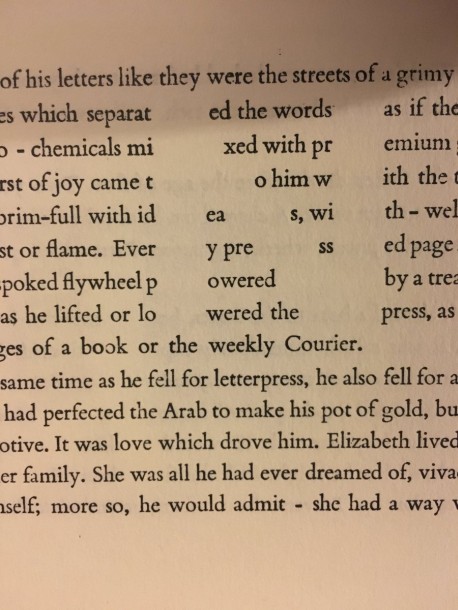

‘The design is stunning, two of the volumes featuring calligrams in the form of images either wrapped by the text, or which the text forms; these images are, of course, a main point of each page. The book is brilliantly constructed so that the image and text therefore complement each other, and the calligrams force the mind to focus on the meaning behind each page.

‘The immediacy of the second person narrative draws you in completely, and I found myself totally absorbed from the first page. The writing is often lyrical, the setting vividly conjured and the wonderful calligrams really add to the experience of reading the book.’ – Karen Langley, Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings

‘Straddling the line between book as object, of literature as idea, and the perhaps more traditional landscape of narrative comfort, The Edge of the Object manages to balance these elements into an absorbing and thoroughly enjoyable work.’ – Alistair Fitchett, Caught by the River

For more information about the novel, which is published by the Half Pint Press, or to buy the three-volume limited edition with handmade case, please visit the dedicated website at The Edge of the Object.

Like Magic in the Streets

Published in autumn last year, Like Magic in the Streets has a somewhat long-winded subtitle: Orange Juice, Aztec Camera, the Go-Betweens, the Smiths, the Blue Nile and the End of Romance. It might just as well be subtitled after situationist Guy Debord’s 1959 film, On the Passage of a Few People Through a Rather Brief Moment in Time, concentrating as it does on a two year period in the first half of the 1980s. So what made that time so special?

Of course, you have to read the book to fully understand the answer to that question – or be a music obsessive ancient enough to remember the years in question. Against the vividly depicted backdrop of Britain in the early 1980s, young Edwyn, Roddy, and Stephen, among others, are brought to life as Tim Blanchard tackles themes suggested to greater or lesser degrees by each of the five albums – love and romance, existentialism, literature, music criticism, and politics, not to mention the nature of being in a band setting out to do things differently. It’s a portrait of a time and inventive artistic creation in difficult circumstances, the like of which will never come again, Tim argues.

The albums may be relatively randomly chosen as a result of personal taste and youthful encounter, but they are bound together by a strong conceptual framework which owes as much to fiction as cultural history. The end result is a text that’s alive to the space between art and what it represents, as well as to the gap between the concrete adventure of being young and in a band, and the abstract expression of that adventure. Like each of the LPs, the book becomes more than the sum of its parts.

Of the five long players in question, You Can’t Hide Your Love Forever remains the most charming in spite or because of its fragility. High Land, Hard Rain is a miracle of youthful maturity; Before Hollywood, a mix of sentiment and astringency set to supremely melodic music and awkwardly perfect rhythms. The Smiths’ debut still sounds something of a flat disappointment to these ears, compared with what it might have been, and what Hatful of Hollow is (bottled essence of magic, courtesy of the BBC sessions machine). Finally, the cityscape reverie of A Walk Across the Rooftops has proven surprisingly timeless given its of-the-time instrumentation, losing none of its mood of yearning melancholia in the intervening years.

You could tell a not dissimilar story using a completely different set of LPs, say, Felt’s The Splendour of Fear, The Pale Fountains’s Pacific Street, Prefab Sprout’s Swoon (Songs Written Out Of Necessity), Everything But The Girl’s Eden (all released in the first six months of 1984), and Del Amitri’s eponymous debut LP from 1985. In those grooves too you can still find plenty of mystery and enigma, youthful urban fire, and all the delicious wordplay you could wish for, not to mention the fashioning of new styles from borrowed clothes alongside the ethereal shimmer or rebel-rousing clang of electric guitars.

In another’s hands, any one of those five could replace any of Blanchard’s – myself, I might have been inclined to drop the Smiths, who have never been short of tomes dedicated to them. I’m sure there were some close calls for the author when settling on his chosen five, and while the Smiths is an obvious and pragmatic choice, you could argue it’s also a necessary one, given their dominance of the independent music scene for the duration of their existence.

Blanchard ends his chapter on the Smiths with a valiant contemporary defence of a man who was clearly a hero of his adolescence just as much as he was of mine. Morrissey hasn’t changed, he argues, while in the meantime, our culture ‘has been radicalised’. He suggests we look to unmediated interviews rather than those edited to create another furore around Morrissey’s perceived hardening into a truculent right-wing racist. But I would argue it’s in the nature of culture broadly (rather than radically) to reflect the times, and just as normative 1950s attitudes to race looked glaringly backward in the 1980s, so too do attitudes stuck in the 1980s now. Morrissey may be honest about his opinions, but he is failing to read the room every time he says something that is likely to be taken as flagrant and contentious, and when it comes to encounters with the media, he’s hardly a naïve ingenue. It better behoves the older generations to learn from the younger than to dig in and insist on their original viewpoints remaining inviolate.

‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.’ The immortal first line of the L.P. Hartley novel from which the Go-Betweens took their name also hangs over the rest of Like Magic in the Streets. Hartley was depicting the Edwardian summer of 1906 midway through the 20th century. In describing how the early 1980s look from the viewpoint of 2021, Blanchard brings alive the hand-to-mouth poverty and the time-rich freedom of each chapter’s set of protagonists. Are these conditions which could ever come again, to forge five comparable sets of music now?

Blanchard seems to suggest not, but clearly there are still plenty of the kind of privations from which young would-be artists yearn to escape, and which the pandemic has only served to exaggerate. The silver lining of the last two years may have been to give music makers of any age the time to gestate and forge something new, albeit in relative isolation. But while in their dead time the independent players of the early eighties had to actively track down influences and inspirations in order to shape them in new ways, 21st century dead time is now awash with streams and rivers and seas of content; how does any young person have the mental space to swim or dive their way to what might prove useful to them among the myriad cultural relics of the past? Is there treasure-hunting life beyond algorithms?

At the outset, Blanchard flags his book as amateur and homemade and non-academic, but his reading of critical and historical sources has clearly ranged far and wide, and all quotations are scrupulously noted. I imagine he wanted to leave himself free to write something expressionistic and novelistic, each album an emotional and narrative strand interwoven with the others; and indeed interspersed throughout the book are evocative fictional scenes from ordinary life, characters navigating adolescence in the eighties who may or may not be about to chance upon at least one of the five LPs in question.

These and a more objective historical contextualising give any reader who did not live through the eighties a strong flavour of the decade, presided over throughout by one single humourless and malevolent prime minister; the bleak attrition of the urban fabric and the economic state of affairs contrasting with the brash colours emanating from TV sets on Thursday nights as, via the medium of Top of the Pops, we watched Duran Duran swan on a beach in Sri Lanka (as Pete Wylie so memorably sang on the Mighty Wah!’s Weekends). It’s a fascinating and thought-provoking read, and of course it succeeds in its main aim: either to make you want to hear all five LPs for the first time, or to return you to each one in order to listen as closely as you did when you originally dropped the needle onto the grooves all those years ago, and listened enthralled as magic poured out of the speakers.

From Mirror Man to Myrrhman

It’s 30 years to the day since Talk Talk’s boundary-pushing Laughing Stock album was released. I was lucky enough to hear it for the first time on my first-ever evening in Paris, and my reminiscences of that evening (and that year) are now up at Caught by the River.

In session tonight

I can tell you exactly where I was at ten o’clock in the evening on 17th February 1986: in a small downstairs room in a rented cottage in Suffolk which was built into the walls of the vegetable and fruit garden belonging to a Georgian mansion. Formerly a pantry, it was now my bedroom. The shelves were intact, but instead of preserves and condiments, they now supported my burgeoning collections of books, records and tapes.

I was seventeen years old and it was the time of day when I, along with many other members of a not-so-secret cabal up and down the land, habitually tuned into the John Peel show. Thanks to a farmboy’s wages, I had a Technics tuner, and – my right index finger poised over the pause button – a tape deck with a cassette cued up to record any song or session track which piqued my interest. I would have known what was coming, because John assiduously let you know in previous programmes what was airing in the next. That Monday night, it was the turn of the Jasmine Minks to be granted the honour of a Peel session – surprisingly their first, given that they already had a mini-LP and three singles to their name, the most recent of which being the garage-punk rush of What’s Happening, which Peel had given plenty of airtime the previous year.

And now, thirty-five years later, the tracks Peel played that night have been excavated from the BBC archives, thanks to the first of two gorgeously presented double-pack singles from Precious Recordings of London. The songs capture the Minks on the cusp of releasing their first full-length LP, adding more ambitious arrangements and increasingly sophisticated playing to the youthful roar of their early singles.

The Ballad of Johnny Eye, written and sung by Adam Sanderson, is sixties-infused bedsit blues for eighties loners, lifted by its plangent lead guitar, and by its beautiful incantation of a chorus – ‘I wish I was the air, so you would breathe me in, and hold me there’ – the kind of words which lodge in a seventeen year old’s head, and stay there for the rest of his or her life.

The first of three Jim Shepherd tunes, Cry For a Man is a rugged sort of ballad, propelled by Tom Reid’s wonderful drumming and brightened by the trumpet the Minks had now added to their sound.

I don’t think any recording of You Take My Freedom quite matched how the song took flight when the Jasmines played live – it was always a highlight of their set, with Jim summoning a full-throttle vocal rasp and marrying it to the Minks’ ever-faster musical ducking and diving – but this version is a vast and filled-out improvement on the rather thin-sounding version on the first album.

It’s hard to convey now, when anyone can immediately hear anything from any time past or present, just how important the evening hours on Radio One were for music obsessives thirsting for sounds beyond those which made the Top 40. Peel in particular aired music which simply could not be heard anywhere else, certainly in my part of the country. Through his own obsession and a kind of public service duty to what was otherwise likely to remain marginalised, he fostered the creation of independent music networks, and allowed far-flung like-minded individuals to connect with each other.

Eight months on from the Peel session, I finally found myself in the same room as the Minks – the delightfully-named New Merlin’s Cave in King’s Cross. I was selling my first fanzine, Lemon Meringue Pantry, for the first time that night, and the Cave was soon full of splashes of yellow, an indicator if ever there was one that there were more like-minded souls here than could be found in the whole of Suffolk. Sadly by this time, Adam Sanderson had left the group – a story in itself – so I had missed my chance to see the Minks in their original line-up. But Jim Shepherd was clearly still on a mission and I drank in both the positivity and the joyful cellarful of noise.

A month after that, the Minks were back at the Beeb, this time for Janice Long, which brings us to the second of Precious’s double-packs. Jim’s songwriting had become more reflective; you might even say mature, as if Adam’s departure had revealed the essential fragility of any creative enterprise, and led him to wrestle lyrically with the past as much as the present. Notably the crack in the ranks would also gave rise to Living Out Your Dreams on the Another Age LP, but here are three songs which match it for everything that was great about the Jasmines, and show how quickly the group were developing.

Follow Me Away is an early example of the seventies-influenced singer-songwriting which came to dominate Scratch the Surface, the hugely underrated follow-up to Another Age. It’s looser, softer, more mature, but just as gorgeous melodically as Jim’s earlier tunes. There’s even some harmonica, in what I imagine is a nod to Dylan.

And here is a first pass at Cut Me Deep; not yet quite the magnificent epic that appears on Another Age, but well on its way to becoming so, even in this shorter version, on which Derek Christie’s trumpet does some of the lifting of the lead guitar on the later take. The song was about Adam; through leaving he had managed to motivate Jim to new heights, and write what has become one of Minks’ best-known songs.

Best of all, though, is a sparse, stately, five and a half minute version of Ballad (aka Soul Station), the kind of song you could play on endless repeat, following the ever-changing path of its weaving melodies without ever getting tired of them.

I still have the tapes on which I recorded those BBC sessions. I suspect if I tried to play them, my old cassette deck would chew up the tape irretrievably. I’ll hazard a guess that one day the whole of the Peel (and evening show) session archives will be digitised and made publicly available in perpetuity, ideally in a freely accessible rather than monetised way. You can imagine music historians of the future having a lot of fun as they unearth and listen its forgotten treasures. But in the meantime, let’s tip our hats to the likes of Gideon Coe on 6 Music and concerns like Precious for giving us glimpses of the gold within.

South Foreland

It could be any old unknown dude on the cover, bearded and with his twelve string acoustic guitar pointing out at you, almost accusatorially.

But it’s not. It’s Oliver Jackson of Emily, once part of the roster on not one but two of the most fiercely independent record labels of the 1980s, Creation and Esurient. They made a masterpiece of a single, Stumble, for the latter, then a near-masterpiece of an album, Rub Al Khali (for the aptly-named Everlasting label) before fading from view.

South Foreland ranges from the Westway to the white cliffs of Dover, before finally setting its sights on America. It’s impressionistic, elliptical, and not easy to pin down, giving it the feel of a work in progress which necessarily had at some point to be surrendered to fixity. But that also gives the eight songs collected here an air of timelessness. It doesn’t hurt that they are as characteristically melodic and melancholic as Emily’s were, at times hauntingly and sorrowfully so, although I concede I might be getting at least a portion of that feeling from the great many years which have passed since I used to stand two twelve string acoustic guitar-lengths away from Ollie in the audience at Esurient’s special nights of action. There was always a blue and a blues sensibility to Ollie’s baritone, and it seems only to have become more pronounced with the passing years, even as he strains for notes higher up the register and makes you think of Bon Iver (though Justin Vernon may well never have listened to Emily, and likewise Ollie to For Emma, Forever Ago).

Synthetic keyboard washes add to the sound picture, inviting comparison to the feel and tone of Cat Power’s more recent work. There’s also a gently shuffling groove to many of the songs, and you can imagine the Emily of old performing them as they used to, dramatising and improvising away from the core of a song until it was something other than what it began life as. The same restless spirit is evident here.

It’s a welcome return, and I hope it proves not to be a one-off. Who knows, when we have live music back, it might even be possible to stand two twelve string acoustic guitar-lengths away from Ollie once again.

- Ollie Jackson – South Foreland (Bandcamp)

Timeless resolve

The Claim – The New Industrial Ballads

The Claim – The New Industrial Ballads

Generally, I’m not a fan of comebacks. Sure, there are exceptions – Johnny Cash, the Go-Betweens, the Wild Swans, off the top of my head – but for every unexpectedly great later work, there are many which make you wish an artist or a group had let their oeuvre be. It tends to be the case that if you stop exercising that song-creating muscle, it’s hard to get it back into the shape it was in when you were working out regularly.

Increasingly though, people do pick up their instruments again, once nostalgia for the old days overcomes the sour memories of the internecine tensions of being in a band; or the thankless grind of forever trying to draw attention to the music is forgotten; or, more practically, because the kids have become independent beings, and time has opened up again.

The Claim – Davids Arnold and Read, Martin Bishop and Stuart Ellis – are in that exceptional bracket. 31 years after their last LP, and ten after the Black Path retrospective, here is (or are) The New Industrial Ballads. (It’s a not untypical title for the Claim, somewhat defiant, a little bit odd. But meaningful, since each of those words – ‘new’, ‘industrial’, and ‘ballad’ – could stand for something else. Art and work and love: three important ingredients in good and fruitful lives.) There’s been no apparent diminishment of their musical nous or chops, while David Read has obviously looked after his vocal chords, because they can still express what they used to be able to as effortlessly as ever.

After an instrumental prelude, the driving beat of Journey kicks in. Its musical rise and fall suggests that it’s the group’s intention to take the listener on a journey, too, through time and space and mood. It’s followed by Smoke & Screens, which starts off as an acoustic paean before electric guitars and strings stir up an emotional storm that’s comprised partly of remorse, and partly weariness. In these two songs you have the album’s lyrical concerns in a nutshell – proudly (but never overbearingly) political on the one hand, and on the other, charting the ups and downs of emotional fortune that tend to accumulate once there is more of life behind than ahead of you.

Like London buses, a third deeply affecting melody arrives alongside the kerb and takes you to The Haunted Pub, where David Read looks back down the years and simultaneously mourns and celebrates the memories such pubs evoke. Light Bending also has the pep and melodious zip of, say, God, Cliffe and Me or Waiting For Jesus from back in the day. Vocally, David Read sounds at turns sure-footed, reflective, vulnerable, as young as he was when the Claim were first making their way in the world, and yet never less than gracefully mature. Musically, the album is rich and beautifully recorded, with a just-so balance between detail and space; the group have clearly taken their time to get everything absolutely right. Is it a better album than Boomy Tella? In its greater variety and lived wisdom, definitely. If it wasn’t foolish to wish that things had turned out differently, I might say it’s a shame or even a crime that the intervening years haven’t given us another half dozen Claim albums of likely the same quality; another sixty odd melodies sung in that wonderful, lilting voice.

If these are The New Industrial Ballads, what were the old? That depends upon which side of the Atlantic you are. Over in America, they were the songs of struggle which emerged from the coal mines, textile mills and farms of the 19th century, kept alive in the 20th by the likes of Pete Seeger. On this side of the pond, we’re talking about the broadside ballads that came out of the Industrial Revolution – broadside as opposed to broadsheet, because the songs were printed solely on one side of paper and sold cheaply. The specific inspiration is Jennifer Reid‘s recent efforts to air the broadside balladry of Manchester and Lancashire, and it’s led to the Claim’s own adaption of an industrial ballad in the form of When the Morning Comes, sections of which recall the spoken word French on the Jam’s Scrape Away, and also remind me of Ultramarine’s Kingdom (featuring Robert Wyatt on vocals). In a similar act of historical reclamation, its lyrics were adapted from The Song of the Lower Classes by Ernest Jones, which Ultramarine discovered in the folk song archives of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library at Cecil Sharp House.

At least one of this new set of songs is an old industrial ballad of the Claim’s own devising: Hercules dates from demos recorded around 1991-92. Brought back to life after all these years, it’s the equal of Aaron Neville’s song of the same name (written by Allan Toussaint), which may or may not have suggested the title and the not dissimilar subject matter:

‘Looking from my window sill

From a tower block I see

Boarded-up shops, run-down housing

There’s your Big Society’

An absolute highlight of the album comes when the pacy Just Too Far abruptly judders to a halt and immediately segues into the down-tempo, mournful Mrs Jones. It’s hard not to see the latter as a companion piece to Boomy Tella’s Mrs Shepherd, and it’s a dose of the kind of Thames delta blues I never thought I’d have the pleasure of hearing again.

On 30 Years, old fellow traveller Vic Templar (aka Ian Greensmith) returns to narrate another story that makes the passing of time explicit. While lyrically the album as a whole does feel like a journey into the past, musically it all sounds too fresh to be regarded merely as a period piece. Eventually the journey arrives back at the beginning, and Estuary Blues and Greens – the scenery that was the backdrop to the Claim’s formative years, and is now an anchor in the present: ‘this place helps me find my feet’. You could add Estuary Blues and Greens to the Action’s legendary Rolled Gold recordings without there being any drop-off in quality or loss of that collection’s visionary, psychedelic mood – it’s that good. As is the song with which the Claim close the album, Under Canvas. It’s a personal ballad in the style of early John Martyn or Bert Jansch, and as touching as anything on Paul Weller’s most recent studio album, the wonderfully folky True Meanings. I’d love to hear more in this style, but then I’d be happy to hear more of the Claim’s music in any style they choose. Here’s hoping we won’t have to wait another three decades for it.

- The New Industrial Ballads by The Claim (A Turntable Friend)

Beneath the branches, and the reach

Can it really be more than thirty years ago that The Claim’s Boomy Tella LP was released? Decades have flown by, but a record I’ve consistently listened to for (considerably) more than half my life now seems to exist outside of time passing. This is the beauty of a favourite recording – its magical moments are frozen, not in aspic or ice but in some living, breathing sense, whether the overriding feeling is upbeat or downhearted. The distinctive first few beats and bars of Not So Simple Sharon Said sound out, and those intervening decades drop away. I could be nineteen again, and tapping my foot to them at The Falcon in Camden, or smiling as John Peel plays the song for the first time on the radio. Every note remains familiar to me. It’s hard to step back and attempt to appraise it afresh, let alone objectively.

Can it really be more than thirty years ago that The Claim’s Boomy Tella LP was released? Decades have flown by, but a record I’ve consistently listened to for (considerably) more than half my life now seems to exist outside of time passing. This is the beauty of a favourite recording – its magical moments are frozen, not in aspic or ice but in some living, breathing sense, whether the overriding feeling is upbeat or downhearted. The distinctive first few beats and bars of Not So Simple Sharon Said sound out, and those intervening decades drop away. I could be nineteen again, and tapping my foot to them at The Falcon in Camden, or smiling as John Peel plays the song for the first time on the radio. Every note remains familiar to me. It’s hard to step back and attempt to appraise it afresh, let alone objectively.

But this is what the reissue of Boomy Tella on A Turntable Friend Records is suggesting I should do. What David Arnold’s touchingly humble sleeve notes (‘This was nearly our great album’) tell me were ‘cheap rattling drums’ and ‘replica guitars’, still sound as thrillingly rich to these ears as they did when I first heard the LP in late 1987. And the remastering has put a little more boom into Boomy Tella, with Stuart’s sure-footed bass playing in particular coming through more clearly than I ever recall it doing on my old vinyl.

The songs are simple, yet surprisingly sophisticated. The singing is heartfelt, yet lyrically speaks so often of doubt. Uniquely, the music mixes the bloodlines of mod pop and English folk song, but much less consciously than that might suggest; while the Claim would have been entirely au fait with the Jam and the Style Council, I don’t imagine David Read had heard much if any folk music before recording Boomy Tella, and yet if you heard it a cappella, his unaffected singing voice might easily lead you to place him within the tradition of English folk song.

No matter what calibre of instruments the two Davids, Stuart and Martin were using, it’s all beautifully played, something fans came to expect of the Claim, having seen so often with our own eyes what a high-functioning, single-minded quartet they were. Here’s how Kevin Pearce, who originally put out the LP on his Esurient label, described it not long after its release, in a piece for my fanzine of the time:

I love the way it’s finely balanced. The way it’s sinewy and substantial but understated and light on its feet. The way there’s something to get your teeth into but something you can’t quite put your finger on. The way it’s so English like Ray Davies, Vic Godard but altogether strange somehow. The way I keep coming back to it like a tongue always comes back to a loose tooth. Most of all I love the way Not So Simple Sharon Says starts as much as I love the way Waterloo Sunset starts.

Boomy Tella’s cover may have been deliberately artless, but that continues to conceal an artful, inventive approach to songwriting. Guitars are picked, strummed, and struck into modernist shades of red and blue, while bass and drums form a rhythmic backbone that is indeed foot-tapping in its simplicity. Over the top David Read weaves a lyrical sense of the absurdity of the everyday into those folkish melodies of his. On one level the group are mates having a laugh, incidentally producing consummate moments of pop music like Beneath the Reach. On another, they’re gifted poets telling it like it is, playing it how they feel it, and coming up with something of the emotional heft of Down By the Chimney.

The Claim achieved a marriage of unforced exuberance and subtlety that set them apart from the majority of both the independent music of the era and the Britpop that was to follow. Where might the Claim be now if they had had the time, space and money to plot a course through the ’90s and beyond? As with so much artistic endeavour, the what-ifs are legion.

Live, the Claim were both engaging and inspiring – and having seen them play again last weekend at the 100 Club, I can report that they still are. For me, no other group of the time and type combined serious musical intent and a sense of ease and enjoyment better than the Claim did at their best. Davids Read and Arnold would introduce what were obviously carefully composed and cherished songs with carefree good humour. Odd rhythms and jazz inflections, indeed odd touches all round, informed what would otherwise have been straight-ahead pop. Dave Arnold held his guitar high against his chest, and the unconventional playing style contributed to the choppiness of the sound. Thanks to the expressive range of Dave Read’s wonderful, lilting voice, the Claim could be both irrepressibly upbeat and as blue as Miles, though cheerfulness would keep on breaking through.

The Claim tried not to let their lack of acclaim get the better of them. They kept on keeping on, playing shows to a small but devoted following, putting out great singles, but eventually, inevitably, there came a period in the early 90s when it must have felt like the returns were ever-diminishing. And so they called it a day and got on with their lives, until the time was right to regroup and – as they say in football after a defeat – go again.

The freshly remastered Boomy Tella comes with a quartet of extra songs: a Jam-my demo of the later B side, Business Boy; an equally robust rendering of God, Cliffe and Me; a fabulously lively take of live favourite Fallen Hero; and an untitled northern soul stomper that I don’t recall ever hearing. It’s all great, and my appetite is well and truly whetted for the group’s new material, especially having heard a handful of the new songs live. It’s due to appear in album form come May. The title? The New Industrial Ballads. The expectation is that they will be at the very least on a par with the old industrial ballads of Boomy Tella.

Earthbound

In Earthbound, Paul Morley takes us down the Tube for a journey on the Bakerloo line, and ends up talking about a John Peel session by Can. ‘Can music remembered music from the future that had not happened yet: by remembering it, as though it was an ordinary thing to remember the future, they made it happen.’

There’s plenty on the experience of travelling underneath the city too, as well as working for the NME; possessing one of the first Sony Walkmans in London; and interviewing Mick Jagger and ‘punkishly, pompously telling [him] off for being too old, at thirty-seven, to be singing pop’.

The comparisons of Brian Eno’s music with Harry Beck’s London Underground map, then of Googling and using the Tube, are typically bravura Paul Morley, not so much spotting patterns as forcing the cultural world to bend itself to his vision of it.

If Words and Music: A History of Pop in the Shape of a City felt at times like too much of that vision for an ever so slightly less pop-obsessed reader to cope with, then Earthbound’s focus and (relatively) contained and constrained subject matter make it an always engaging read.

Technique

I first heard Prefab Sprout on a cassette that a school friend made for me. Tibor put Swoon on one side, and the Pale Fountains’ Pacific Street on the other. Songs Written Out Of Necessity soon became songs listened to out of necessity. I used to sit next to Tibor in maths; he was of Hungarian origin, and his family ran a restaurant in town called the Silken Tassel. I don’t know what became of him after we left school. He could almost be a character with a walk-on, walk-off part in one of the more nostalgic songs on Swoon; ‘I never play basketball now’, say.

I first heard Prefab Sprout on a cassette that a school friend made for me. Tibor put Swoon on one side, and the Pale Fountains’ Pacific Street on the other. Songs Written Out Of Necessity soon became songs listened to out of necessity. I used to sit next to Tibor in maths; he was of Hungarian origin, and his family ran a restaurant in town called the Silken Tassel. I don’t know what became of him after we left school. He could almost be a character with a walk-on, walk-off part in one of the more nostalgic songs on Swoon; ‘I never play basketball now’, say.

Today, I more readily associate the Swoon-era Prefabs with the word-heavy, melodic alternatives provided by early Del Amitri and Microdisney than with the Paleys. Because of the relative maturity of Paddy McAloon’s song craft, you could tell that the Prefabs had greater commercial potential than any of those groups, and eventually – four years down the line – Paddy’s ship did indeed come in, in the form of ‘The king of rock’n’roll’. But there were three long players before that moment, two released and one rejected. After all these years, and prompted by a friend who’s been retrospectively puzzling over Swoon like a dog gnawing away at a bone, I think it’s time for me to square up to each in turn, starting with that first LP.

What I like about Sondheim is that he can put a set of precise emotions into a song lasting a certain number of minutes. If he had an odd shaped sentiment, he would construct an odd shaped melody to accommodate it. There was never any sense of it being a happy accident. – Paddy McAloon, 1983

That absurd, prog-sounding name. It’s like those early automatically generated internet passwords which paired two random words. Yet at the same time, it suits, as does the fact that the group contained a pair of McAloons, brothers who appear to have lived a rather Danny the Champion of the World childhood a little way outside of the cathedral city of Durham.

The album opens with ‘Don’t sing’. Not ‘Sing’, but ‘Don’t sing’. A negative right there at the start (give or take the two preceding singles), a negative immediately disregarded. Some might say that comprehensibility is disregarded too. ‘An outlaw stand in a peasant land / In every face see Judas / The burden of love is so strange.’ Individual lines and couplets make sense, but put it all together and it’s hard to elicit or discern what Paddy’s driving at. We seem to be in the southern states of the US, or possibly Mexico. Too much is being asked of someone, the outlaw, presumably; a guise for Paddy himself? It could almost be a scene from a Cormac McCarthy novel, but in fact these are scenes from Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, whose central character is a self-destructive ‘whisky priest’. Paddy had obviously read widely – in early interviews, he mentions Joyce, Knut Hamsun, Nabokov, and Thomas Hardy – and it’s clear that imaginative worlds were informing his songwriting just as much as the real one around him.

In 1984, I was immediately captivated by how singularly crafted the whole of Swoon was, in comparison to pretty much everything else around. The lyrics for every song on the album were rich in allusion and poetic intent. I may have been puzzled by the lyrics, but it seemed complete, a perfected work, with nothing out of place, and no redundant embellishments. The imagery, the melody, the odd arrangements and structures, the dulled funk of the subdued but equally melodic bass, the contrast between the amateur sheen of the cheap keyboards sounds and the complex proficiency of temporary member Graham Lant’s drumming; it sounded like nothing else. Despite all the lyrical questing and questioning, the songs and the way they were sung was assured; a benefit I would guess of their long gestation period, but also of Paddy’s seemingly gargantuan self-belief and confidence in his own abilities, as this unguarded quote from an early interview suggests:

It might sound a bit pompous, but I really am ambitious to be acknowledged as the best. It’s not that I think I’m as good as the real greats – people like Steven Sondheim, Burt Bacharach and Paul McCartney – but when I look at the competition around at the moment. I don‘t really see anybody to fear. – Paddy McAloon, 1983

It’s no accident that ‘Cue fanfare’, which is gently nostalgic in the verse, tips into a bright and blaring celebratory chorus about chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer. When Paddy sings, ‘He’ll take those Russian boys and play them out of town’, he is surely signalling that it is his ambition to be a songwriting grandmaster. And who could deny that he became one?

On ‘Green Isaac’, the singing takes centre-stage, as Paddy’s grown-up choirboy is ably and ethereally echoed by Wendy Smith’s complementary backing vocals. (Not just on this album but those to come, Paddy’s vocals would habitually be lain on the soft mattress of Wendy’s, as she double-tracks many of his lines.) The song seems to concern the lot of a songwriter naively setting out on his journey ‘to be someone’. Perhaps Paddy is looking back and seeing himself as Green Isaac, ‘still wet behind the ears’.

On ‘Green Isaac’, the singing takes centre-stage, as Paddy’s grown-up choirboy is ably and ethereally echoed by Wendy Smith’s complementary backing vocals. (Not just on this album but those to come, Paddy’s vocals would habitually be lain on the soft mattress of Wendy’s, as she double-tracks many of his lines.) The song seems to concern the lot of a songwriter naively setting out on his journey ‘to be someone’. Perhaps Paddy is looking back and seeing himself as Green Isaac, ‘still wet behind the ears’.

For ‘Here on the eerie’, presumably Paddy meant to play on the word eyrie; the title works either way. He voices the dilemma faced by any artist – by any person in so many walks of life – between choosing what is safe and comfortable and unthreatening and normal, or deciding to take the first in an ongoing series of risks, and put yourself out there where there is no safety net, no comfort blanket, and always plenty of threat; a place where you decide what is normal for you. ‘A universal prescription continues to elude… Face yourself or give it away.’ The complexity of the dilemma is underscored by the choppy challenge of the music, and the plangent, questioning critique posed by Paddy’s lead guitar late on.

‘Cruel’ somehow manages to walk the line between archness and sweetness, iced as it is with Paddy and Wendy’s sugar-coated sixties ‘ba ba ba’s. It also manages to address the confusion of a desirous male feminist and the seeds of what came to be called political correctness with the lines ‘But I don’t know how to describe the Modern Rose / When I can’t refer to her shape against her clothes / With the fever of purple prose.’ Made politically aware by punk and all that followed in its wake, this was a bind that many of Paddy’s listeners might also have felt themselves trapped within, over-sensitive and straight-jacketed by a reaction against the blithe and casual sexism of the age, and left unsure as to how to voice their yearning. The song’s archness undoes Paddy’s assertion that ‘There is no Chicago urban blues / More heartfelt than my lament for you’; he seems rather more concerned about the theory and niceties of love than the love itself. This is how he attempted to explain it back in 1984:

It expresses a very down to earth sociologists’ approach to rock, expressing a very basic human feeling. Music can do little more than tell narrative tales about things that are happening. I think you can go beyond that — the difficulty is when it starts to become too vague. You can describe things in another way from that journalistic/sociologist approach. I like to score between the two — I like things that leave you with a strong emotional sense. The correspondence between the words and the real world. Our songs don’t have a definite message — you have to look much deeper.

Just how odd is the intro to ‘Couldn’t bear to be special’, with its choral ‘bo bee’s? Again, it’s like nothing else before or since. Paddy’s vocal goes on to be gently argumentative, until suddenly he unleashes a whole load of pent-up angst that on top of ‘Cruel’ gives you to think that, at the time he wrote these songs, to love or be loved did not come easy for the songwriter. The song also features the line ‘Words are trains for moving past what really has no name’ which only adds to the feeling that despite all of his undoubtedly erudite efforts, what Paddy is reaching for is frustratingly out of his grasp, as by definition the ineffable must always be.

‘I never play basketball now’ starts in a deliberately humdrum fashion before bursting to life with inspired chord progressions and changes of pace. Lyrically, it’s a slam dunk elegy for lost youth, and an evocation of what we all lose as we move from childhood into adult life. Basketball ‘joins the list of things I’ll miss like fencing foils, and lovely girls I’ll never kiss,’ sings Paddy, and we may never have fenced, Paddy himself may never have fenced, but we instinctively know what he means, and I certainly knew and felt it then, in 1984, a time when I was starting to make my own transition from childhood to adult life.

A cheery, whirling Wurlitzer keyboard line meets a bubbling, burbling bass in the uptempo of ‘Ghost town blues’, where listlessness meets meaninglessness and death, and ‘we’re all caught in history’s web’. The prolific songwriter concludes, ‘Perhaps I should learn to shut my mouth.’ No chance of that.

‘Elegance’ is the very definition of its title, with its piano (rather than the cheaper keyboard sounds elsewhere) and its clipped, killing couplets; elegance here is aligned with ownership of the world, while, in contrast, kid, you own nothing – but don’t be seduced by silver service or salvers, because real life and real loving happens out of the purview of those with money and property.

Meanwhile, the narrator of ‘Technique’ appears to have lost out on a woman’s love to the astronomer she has married, and he’s upset because scientists’ eyes ‘don’t fill with wonder when you speak’, and yet at the same time, he’s all too consciously aware of his own intellectual limitations when in her presence. The scientist is unmoved by beauty, and the artist, too moved to make sense. Despite this dim view of scientists, I think we can infer both from this narrator and subsequent star-referencing releases that if he was not intent on being a songwriter and perhaps a pop star, Paddy would have liked to be an astronomer. If we add that his schooling was within the cloisters of a Catholic seminary, then we could say that he chose art over both science and religion. Art which he saw as a craft; a technique, indeed. With the choice resulting in songs as beautifully realised as this – propelled particularly by Graham Lant’s brilliant drumming – music’s gain is God’s and science’s loss.

Proceedings conclude with the second part of ‘Green Isaac’ and in this coda, there is a warning: only fools reach for the moon or the stars. But our sense is that the singer is bound to shoot for the satellite anyway, in what appears to him to be that necessary attempt still ‘to be someone’.

Thirty-odd years after its release, the album leaves me with two abiding (and not unconnected) impressions. One is of a character who has already discovered that love is rarely simple and often imbalanced in some way; the songs feature characters who want to love, but fear failure, and perhaps are struggling to admit anyone to the fortress of the heart, finding fault with an elegant woman for being too elegant, a loving one for loving too much, a beautiful one for being too beautiful, and so on. The second is of a powerful and complex artistic intent. Swoon is definitely a statement, although it voices too many doubts and contradictions to be taken for a manifesto. Someone with that kind of artistic vision is likely to find love difficult, because both are states which attempt to subsume and subdue everything else that might be deemed important. Swoon is the sound of art and love clashing.

On Steve McQueen, a more relaxed songwriter would emerge, one less troubled by the anxieties to be found within Swoon’s grooves. And I would hazard a guess that like many people at a similar age, it was not that Paddy stopped having more questions than answers, but that he began to accept that such answers as he had were good enough to work with, and that perhaps some questions weren’t ever meant to be answered in the first place.

With thanks to Sproutology for its comprehensive archive of interviews.

As rare as hen’s teeth

Tim Hopkins of The Half Pint Press has been kind enough to print up and publish ‘Letterpress [n]’, one of my Missing letters stories. Having faced down the many challenges involved in realising his boxed version of The book of disquiet, typically Tim gave himself a fresh conundrum to solve, one requiring some serious letterpress jiggery-pokery in order to achieve the finished result:

You can find further details and photos here. If you’re interested in getting hold of a copy, let me know via A wild slim alien’s First contact page, and I’ll pass on the relevant information just as soon as I have it from Tim.

To celebrate its appearance in print, and also The Half Pint Press publication of Peter Miller’s short story ‘Dusty Springfield’, a launch party is being held at the bookartbookshop on Thursday 12th October 2017. Do come along if you’re in London, as it will be a chance – rare as hen’s teeth – to hear me read…

By the way, you can also find me on Twitter here: @awildslimalien

Out in the wind

Ever wondered whether there might be a cache of unreleased Del Amitri songs dating from the seemingly fallow period between the release of their eponymous debut album in 1985 and their reinvention as the rather more adult-oriented proposition which culminated in their second LP, Waking hours, in 1989?

Well, there is. Not so long ago, I came across a reissue of Del Amitri’s first single, ‘Sense sickness’, in my local record shop. The artwork included a set list with titles to a couple of songs I’d not heard before. Online research led not to those songs, but to a blog post from 2010 by my Firestation Records friend Uwe about the Dels’ lost second album, and a link left in the comments to an extremely low-fi download of the songs he mentions, plus one or two more. And then, on a hunch and a quick google to – miracle of miracles – much better quality YouTube uploads of the songs.

Even if the songs don’t quite match up to those on the debut album (which I wrote about here), its admirers will find much to like and perhaps even love in this lost second album. In fact, the more I listen, the more I think these unreleased recordings merit comparison with the (once) lost early demos of Hurrah!, or the shelved post-Steve McQueen Prefab Sprout album which finally saw release as Protest songs, after Paddy and the gang had temporarily become the kings of rock’n’roll.

Save for ‘Nothing goes accordingly to plan’, which crept out at the time on the ‘Abigail’s birthday party’ cassette-only compilation, they’re roughly recorded and nothing like as detailed or filled out as the songs on Del Amitri, but the sparseness serves to differentiate these recordings, and makes you wonder what might have been had they been taken into the studio proper. That they were not quite of the same refined quality, or that they didn’t move the group forwards quite enough might be reasons why that never happened, but this cache still feels like long-lost treasure now found.

Save for ‘Nothing goes accordingly to plan’, which crept out at the time on the ‘Abigail’s birthday party’ cassette-only compilation, they’re roughly recorded and nothing like as detailed or filled out as the songs on Del Amitri, but the sparseness serves to differentiate these recordings, and makes you wonder what might have been had they been taken into the studio proper. That they were not quite of the same refined quality, or that they didn’t move the group forwards quite enough might be reasons why that never happened, but this cache still feels like long-lost treasure now found.

The ever-shifting guitar lines and vocal melodies of Del Amitri remain a key ingredient. ‘I am here’ starts messily with a mish-mash of double-time instrumentation before settling into something as plangent as anything on the debut, including ‘I was here’, to which with its present tense title this song is surely a sequel. Featuring a vocal full of yearning and a lyric about standing your ground – ‘I am here, right where I wanted to be’ – it shows that singer and songwriter Justin Currie still had an excess of words and emotion to spill.

On ‘My curious rose’, a quiet groove is established between the weaving lead guitar and sticks tapping out the rhythm on the side of a snare, a groove from which the chorus joyously bursts forth. ‘Tall people’ is slightly odd lyrically (‘Walk into a hospital and give yourself up…’), but is still another wonderful confection of melody and intricately woven guitar. ‘Tears And Trickery’ concerns ‘an impossible girl’ and features fabulous falsetto and guitar lines quite as jaunty as those on the debut’s ‘Hammering heart’.

The set of ten songs ends with ‘The wind in the wheels’, which has the breeziest of choruses and would have made a great double A side with a number apparently not slated for inclusion on the lost album, ‘Out in the wind’. The latter song did in fact see the light of day at the time, though somewhat hidden away on a subscription-only Record Mirror EP. Cleanly recorded, and with initial restraint giving way to a stormy chorus, it offers the best insight into just how good the-album-that-never-was might have turned out to be.

The set of ten songs ends with ‘The wind in the wheels’, which has the breeziest of choruses and would have made a great double A side with a number apparently not slated for inclusion on the lost album, ‘Out in the wind’. The latter song did in fact see the light of day at the time, though somewhat hidden away on a subscription-only Record Mirror EP. Cleanly recorded, and with initial restraint giving way to a stormy chorus, it offers the best insight into just how good the-album-that-never-was might have turned out to be.

With my taste far broader and more accommodating than it was when I was a ferociously intense and militant teenager, in retrospect I like much of what Del Amitri went on to record in their mature guise, especially the sequence of grown-up love songs that they put out as singles. But if you stipulated that I had to make a cut-and-dried choice between the debut and this lost second album on the one hand, and all of what came after on the other, the teenager in me would still insist on keeping hold of the Dels’ precocious juvenilia every time.

- Del Amitri – Lost second album (YouTube playlist)

- 1985-86 demos and rehearsals (Download – right click and save)

Foxy

February 5th sees Firestation Records’ release of A retrospective by Emily, on both double CD and vinyl. I was asked to pen the sleeve notes, and happily obliged, what with ‘Stumble’ being among my favourite ever singles, and Rub al Khali one of my favourite ever LPs. It’s the first time on CD for both the single and the album.

February 5th sees Firestation Records’ release of A retrospective by Emily, on both double CD and vinyl. I was asked to pen the sleeve notes, and happily obliged, what with ‘Stumble’ being among my favourite ever singles, and Rub al Khali one of my favourite ever LPs. It’s the first time on CD for both the single and the album.

Expertly transferred from vinyl (as opposed to inexpertly by me, which had initially threatened to be the case) owing to the master tapes being lost, the three songs from the ‘Stumble’ single sound fantastic, better than I could possibly have hoped. Rub al Khali also benefits from the absence of snap, crackle and pop, and remains a thing of wonder, as timeless and out of time now as it was when it was released 25 years ago.

If that weren’t enough, A retrospective additionally includes a selection of demos of varying sound quality and excellence, ranging from the group’s earliest recordings through to ‘You don’t say you need that’, a song which dates from long after Rub al Khali and gives a sense of what might have been had the album – not to mention singer-songwriter Ollie Jackson’s talent – garnered the attention it deserved. A number of otherwise unrecorded live favourites also grace the compilation, including ‘Merri-go-round’ in both its early and mature forms, the latter version having been scheduled as Esurient’s follow-up to ‘Stumble’. The track which closes the second CD is another highlight – a beautiful acoustic version of ‘Rachel’, one of the ‘Stumble’ B sides.

What the compilation sadly lacks is the Irony EP which Emily recorded for Creation Records in 1988, but ‘Mad dogs’ at the foot of this post stands in part to remedy that absence. To further whet your appetite, you’ll also find an outtake version of ‘Foxy’, the majestic opening song from Rub al Khali.

What the compilation sadly lacks is the Irony EP which Emily recorded for Creation Records in 1988, but ‘Mad dogs’ at the foot of this post stands in part to remedy that absence. To further whet your appetite, you’ll also find an outtake version of ‘Foxy’, the majestic opening song from Rub al Khali.

I’m proud to have been involved with the putting together of this release, but even if I had not been, I would still be wholeheartedly recommending it to you. Every (Pantry-reading) home should have one.

- Foxy (outtake version)

- Mad dogs (from the Irony EP)

- Really mad dogs (dance mix 1) (from the Something Burning in Paradise compilation)

- Pre-order A retrospective by Emily from Firestation Records (NB The Rub al Khali tracks are not included on the vinyl version of the release)

Let me imagine you

An evening with Robert Forster

Over the three decades preceding this one, I was lucky enough to see the Go-Betweens in a variety of different venues, ranging from a nose-to-fretboard experience in the Rough Trade shop in Ladbroke Grove to a sit-down affair with strings at the Barbican. But this Robert Forster show is a live performance first for me – he’s playing a Quaker meeting room, specifically the one in the centre of Oxford. The plain, wood-panelled hall is lit only by a chandelier which has eight of its twelve bulbs missing, but tonight it’s packed with Friends of a different kind than those to whom it usually bears witness.

Wearing a dark v-neck and a white shirt, Robert Forster enters the room from stage right and studiously addresses the microphone. ‘Tonight I’m going to be speaking about anthropology.’ Then he gathers himself with a deep breath, and proceeds to play ‘Spirit’, the first number in a set of twenty songs which is never less than captivating, and comes absolutely alive as both the audience and perhaps the man himself realise that he’s still got it, sometime between the end of the first song and the start of the second. Though he modestly intimates that the audience should pipe down rather more quickly than they do, Robert nevertheless responds to the effusive warmth shown him, relaxing into a performance marked by its perhaps surprising range and diversity, given that it’s just him and an acoustic guitar. And they are performances of the songs, nuanced and emphasised in the expressive, actorly fashion that we’ve come to know and love, but which is far more apparent in the context of a one man show.

‘Head full of steam’ is the earliest of his songs given an airing, while ‘The house Jack Kerouac built’ is also delivered to great delight during the encore. Naturally a good half of the songs from Songs to play feature, including its lead-off track ‘Learn to burn’, which Robert tells us was the last he wrote for the LP, adding ‘I didn’t know I could still write a song like that’. Then there is my favourite from the album, ‘Let me imagine you’, whose punchline he delivers with immaculate timing:

‘I heard you went shopping and bought such beautiful things

Let me get calculator and add up the cost of all those things

Oh my!’

Otherwise the songs are picked largely from the second phase of the Go-Betweens and the first phase of his solo career, with nothing from The evangelist (somewhat surprisingly, given the setting), perhaps because those will have been the songs that Robert has leant on when performing live over the seven years between it and Songs to play.

The penultimate number is the cartoonish but touching nostalgia of ‘Surfing magazines’, and as Robert strives to do the impossible and simultaneously sing both lead vocal and the ‘da-daaa, da-daaa, da-daaa’ chorus, the audience softly, gently comes to the rescue, gaining in confidence when Robert says, ‘You could go a little louder,’ and so we do, and they’re not an untuneful bunch, his fans. In fact it sounds great, even if I do say so myself, an instance of appropriate harmony in this religious meeting room, a sending up of joyful noise to the heavens. The end of the song is greeted by rapturous applause on both sides.

Robert closes with ‘Rock’n’roll friend’, and as he has intimated, subsequently reappears behind the stall selling LPs and CDs, there to greet a long line of admirers who hang around to have Songs to play signed and be snapped with the great man. I am one of these, managing to be more or less coherent when my turn to chat to him comes around. After he has signed a copy of his book, The ten rules of rock’n’roll, with a dedication to my daughter, he sets himself into a comedic pose for our photo, using those pensive eyebrows to great effect, and (seeing them out of the corner of my eye) making me laugh. I’ve met one of my rock’n’roll heroes. Oh my!

Robert closes with ‘Rock’n’roll friend’, and as he has intimated, subsequently reappears behind the stall selling LPs and CDs, there to greet a long line of admirers who hang around to have Songs to play signed and be snapped with the great man. I am one of these, managing to be more or less coherent when my turn to chat to him comes around. After he has signed a copy of his book, The ten rules of rock’n’roll, with a dedication to my daughter, he sets himself into a comedic pose for our photo, using those pensive eyebrows to great effect, and (seeing them out of the corner of my eye) making me laugh. I’ve met one of my rock’n’roll heroes. Oh my!

Let me imagine you:

Let me imagine you – fragment of solo live performance at the Quaker meeting house:

Alone and unreal

This blog would probably not exist were it not for the Clientele. Their music has sustained me long past the time when I imagined I might still be writing about music in this broadly review-ish sort of way. And this despite the fact that the group once saddled me with an expensive bill – not that they ever knew they had (until now). Out and about in my car one fine spring day in 2007, with the freshly released God save the Clientele playing rather louder than it ought to have been on the stereo, I backed out of a parking space and didn’t spot an already battered Merc doing the same. An unholy alliance of insurance company and the Arthur Daley driving the Merc subsequently saw me stitched up like the proverbial kipper. Masterpiece though it may be, the album ended up costing me considerably more than the £10 I was comfortable spending on it.

This blog would probably not exist were it not for the Clientele. Their music has sustained me long past the time when I imagined I might still be writing about music in this broadly review-ish sort of way. And this despite the fact that the group once saddled me with an expensive bill – not that they ever knew they had (until now). Out and about in my car one fine spring day in 2007, with the freshly released God save the Clientele playing rather louder than it ought to have been on the stereo, I backed out of a parking space and didn’t spot an already battered Merc doing the same. An unholy alliance of insurance company and the Arthur Daley driving the Merc subsequently saw me stitched up like the proverbial kipper. Masterpiece though it may be, the album ended up costing me considerably more than the £10 I was comfortable spending on it.

Ever since, I have superstitiously refrained from playing the Clientele’s music in the car. So I’ve been listening to Alone and unreal: the best of the Clientele only while safely sitting at my desk at home, much as I would like to take it with me everywhere I go. When I first saw the track listing, I wondered if the group had been a little parsimonious in selecting only 11 songs – surely it could have been twice as many, and still have given any Clientele admirer acting as compiler headaches as to what to leave off? But upon listening, it becomes clear what has been done, which is effectively to programme a new album out of songs their fans will have played so frequently that they know them inside out. The music from the group’s different phases flows together, individual songs cast light on their neighbours, and the overall effect is to create both a journey through their output and a recognisable narrative. Having realised this, it wouldn’t be fair, would it, to carp on about this track or that being left off. But bloody hell, no ‘Lacewings’? No ‘Porcelain’? No ‘My own face inside the trees’? No ‘I hope I know you’? No… Stop that. Now.

The compilation picks a chronological path, which suits their development from songs recorded in a seriously lo-fi fashion to the aurally perfect productions of more recent times. It begins with ‘Reflections after Jane’, which sees the Clientele at their softest; for me, the song is redolent of London in the late nineties. The mood of minor melancholia, the resignation rather than racking sobs at the loss of Jane make for a beautiful piece of music, particularly when a middle eight of a kind arrives and takes this listener through the permeable glass panels of memory and into the precise mood engendered by a turn around Waterlow Park in Highgate, north London, 1999.

On ‘We could walk together’ we are again in a submerged, aquamarine sonic world of the Clientele’s own devising. This was the period in which Alasdair used to part-sabotage, part-enhance his vocals by putting them through a guitar amp, making it sound like he was ringing them in from a red public call box (put your nose to the air of these early songs, and you catch the faint smell of piss rising from the concrete floor to mingle with cigarette breath on the receiver). The guitar is crystalline, picking up glints of both sunset and moonlight, and then there are those gorgeous words borrowed from French poet Joë Bousquet: ‘like a silver ring thrown into the flood of my heart’, a line which fits so well with the rest of the song that you wouldn’t know it was an appropriation unless it had been pointed out to you.

The mood again returns to absence, loss, and weirded-out isolation for ‘Missing’, the only choice from the group’s first album proper, The violet hour. The song slowly and subtly unwinds, with accents picked out on an acoustic guitar; what for many groups would be a run-of-the-mill album track is transformed through sheer loveliness into a song which can justifiably feature on a ‘best of’.

Now comes what I think of as Alasdair’s lyrical and the group’s musical tour de force – ‘Since K got over me’. Musically, it’s the closest we get on this collection to the dynamism that they could generate merely out of guitar, bass and drums in a live setting. Alasdair’s guitar clangs and twangs, James ferments another of his ever-melodious bass lines, and Mark’s drums are as bouncy as the trampoline Alasdair refers to in the lyric. Although this is on the surface a song about the aftermath of a relationship, I’ve often wondered whether the initial ‘K’ was deliberately chosen as an allusion to Kafka’s ‘Josef K’, and so to existence as the author of The trial and ‘Metamorphosis’ painted it. ‘I don’t think I’ll be happy anyway / Just scratching out my name’, Alasdair sings, entirely believably. Then ‘There’s a hole inside my skull with warm air blowing in’ gives us a Buñuel-esque vision of a character continuing to sing even though he’s been shot in the head, to the point that you feel he is actually enjoying the curious feel of the air rushing through the hole, past the remaining bone and matter. The end result is both philosophically provocative and an incredible pop song.

‘(I can’t seem) to make you mine’ marks the moment when the group expanded its palette to include strings arranged and conducted by renaissance man Louis Philippe. The result is the Clientele at their most refined, elegant and stately – you could imagine an airing of this song in Bath’s Pump Room not leading to too many tea cups rattled in horror. Once again, the strings evoke the loss, or rather, the never having gained, as well as ‘the ivy coiled around my hands’.

On ‘Losing Haringey’ Alasdair performs a spoken word lyric over more gorgeously melodic music, which somehow enhances the sense of disquiet, lassitude and plain weirdness

of his story. Once again, London is a strongly depicted character, and as I listen, my own feverish wanderings about Haringey and Islington become jumbled up with his character’s: ‘I found myself wandering aimlessly to the west, past the terrace of chip and kebab shops and laundrettes near the tube station. I crossed the street, and headed into virgin territory – I had never been this way before. Gravel-dashed houses alternated with square 60s offices, and the wide pavements undulated with cracks and litter. I walked and walked, because there was nothing else for me to do, and by degrees the light began to fade.’

Lyrically, what is gradually being revealed through this particular choice of songs are the existential battles and romantic adventures of the persona inhabited by the group’s singer. Alasdair has consistently espoused a philosophical as well as literary view of the world via the medium of pop music, and Alone and unreal’s trajectory only serves to hammer that point home, both through the choice of those words for the title of the collection, and through the themes which keep on surfacing from first note to last, themes which have also informed the sequence of Clientele cover art which began with Belgian artist Paul Delvaux’s ‘The viaduct’ for Strange geometry and is maintained with John Whitlock’s faceless, de Chirico-esque collage for Alone and unreal.

Well now, but here’s a change in the mood, a twist in the plot. ‘Bookshop Casanova’ breezes in with a lyric best summed up by the lines ‘ah come on darling / let’s be lovers’. The strings, the strident drums, and a guitar solo half-inched from the Isley Brothers’ ‘Summer breeze’ only go to enhance the fabulous seventies disco mood. In intent and effect, the end result is not dissimilar to Whit Stillman’s literary take on Studio 54 in his film The last days of disco.

By the time ‘The queen of Seville’ comes round, and in spite of its blue lyric, it’s starting to feel like this just might be a tale with a happy ending; the music has a palpable yearning quality to it, and even if ‘it’s gonna be a lonely, lonely day’, at least ‘she sends me roses’. Gentle piano figures and slowly stretched-out limbs of pedal steel underscore the waiting, as do the verses sung under Alasdair’s breath, as if to himself, or his lover, before he lifts his eyes and his voice again to curse his luck.

‘Never anyone but you’ is a thing of perfection, simultaneously sinewy and musically delicate. The character’s mind is still haunted by his surroundings, by phantoms and imaginary choirs – presumably singing these very harmonies, prompting Alasdair to take them down verbatim – but now a chorus line of ‘I can only see you’ continually rings out, giving the song an overriding feeling of almost stalker-like obsession.

‘Harvest time’ manages to be plangent, spooked and spooky – ‘Bats from the eaves go shivering by / Scarecrows watch the verges of light / I hear a choir on the heath at night / But no one’s there’ – and yet somehow also celebratory, in a hallucinogenic, heat-hazed way. An actual choir in the form of backing vocals from Mel and Mark softly and beautifully reinforces this sense of the cyclical nature of life, as well as the philosophical acceptance that ‘Everything here has a place and a time / We’re only passing through’.

The most recently recorded song, ‘On a summer trail’, brings the album to a close. To these ears, it does feel a little like an added extra – while it’s a good Clientele song, it’s perhaps not exceptional, like the rest. That said, it may well grow on me the more I hear it, as so many of their less immediate songs have, and besides, it also fits the narrative, concluding the story on the positive, forward-looking note that ‘Bookshop Casanova’ first heralded.

The CD comes with a free download of The sound of young Basingstoke, formative recordings which date from 1994, although the group were by then sufficiently inspired to have already come up with early favourites like ‘Saturday’ and ‘Rain’. Anyone who already has a copy of It’s art Dad might be a little bit underwhelmed by Basingstoke, as there are a number of tracks in common, and nothing which really bests the early gems captured on Suburban light. That said, songs like ‘The evening in your eyes’, ‘When she’s tired of dancing’, and ‘From a window’ are well worth hearing again.

I can’t help envying the listener who comes to Alone and unreal having heard little or nothing of the Clientele before, because if they like what they hear, then the pleasure of discovering their five albums – so selectively plundered for this compilation – remains open and ahead of them. I’d love to be able to take that journey again, but equally, I’m happy I was along for the ride in the first place.