Strange garden

Although not as fully realised as the Wild Swans’ The Coldest Winter for a Hundred Years – one of my favourite albums of the 21st century – Death Must Be Beautiful, a resurrected solo work from 2004, sees Paul Simpson in equally strong songwriting form. Emerging out of a depression following the death of his father, lyrically it’s bleaker than The Coldest Winter, with references to whirlpools, decomposition, syringes, and poison, and that’s just from the titles on side one of the LP.

The gloom and doom is leavened by Paul’s habitually buoyant melodies and a predominantly acoustic musical prettiness. The players include Wild Swan Ged Quinn on piano and the Granite Shore’s Nick Halliwell on guitar, and it’s produced with a gossamer-light touch by another legend of the Liverpool music scene, Henry Priestman (songwriter and former member of Yachts, It’s Immaterial, and the Christians).

While two or three of the 14 songs are a little on the slight side, even these more fragmentary ones are never less than engaging. Paul’s songs often tend to look back with a kind of nostalgia that finds grim solace in how hard things were back then, noting as they go the beauty in austerity, and these are no exception. Extreme situations force heightened feelings and responses. Wounds either linger without healing, or are opened up to be re-examined as if they had never mended in the first place.

There’s no conclusive rallying cry here, nothing which suggests resolution or a path out of depression, save the music and the process of creation itself. Death Must Be Beautiful catches Paul progressing towards The Coldest Winter…, and its songs (which include a version of Disintegrating with the melancholia heaped higher than on the Tracks in Snow version) both presage and come close to matching the perfection that the Wild Swans achieved on that album.

The LP is pressed in suitably funereal green vinyl. Signed copies of Paul’s artwork for the LP are available as a separate print, with his cheerfully bleak notes about the songs on its flipside. All in all, it’s a beautiful living thing.

Table

Rachael Dadd’s ‘Table’, as mentioned here and there, is downloadable everywhere via Wears the trousers.

White horses kicking at our ankles

Rachael Dadd’s Moth in the motor package is high on concept. A ten inch vinyl record with a choice of hand-printed or artist-created covers, an accompanying exhibition and a digital download which includes an animation by Betsy Dadd, it majors on Rachael’s piano-written songs, while the tour running alongside the record’s release reinforces the point that piano is her current instrument of choice. The release brings together three excerpts from her last album, After the ant fight, one from the preceding The world outside is in a cupboard, and three new songs. The stunning ‘Table’ from After the ant fight leads off, and seems to take on extra zip, punch and flight from the vinyl pressing. It’s entirely appropriate that Rachael’s sister should so painstakingly and fluidly animate that song, given its intimately domestic subject matter.

None of the other re-released songs quite match ‘Table’ for impact; solid album tracks that they are, the lesser of them seem a little exposed in this piano sampler format. To my mind Rachael is a more distinctive songwriter with strings and a fretboard in her hands; when sat on a piano stool, she strays towards territory in which ten-a-penny singer-songwriters are camped. But as if to defy me thinking that, she really stretches out over the keys on the ten inch’s title song. ‘Moth in the motor’ combines the dynamics of ‘Table’ and the animated insect chirpiness of ‘Ant and bee’ from After the ant fight, but with added Thelonious Monkiness, and maybe dashes of Laurie Anderson and Jane Siberry. Well worth seeing Rachael attack the ivories on this song in a live setting, I should think.

The covers are great – a fabulous range of designs and takes on the title – though you may balk at paying some of the quoted prices. I plumped for a cheaper Dadd design and got a rather fetching purple deer-owl hybrid, but if I’d had money to spare for one of the artist creations, I’d have gone for Emma Lawton’s, as featured at the head of this post, for it too is high on concept.

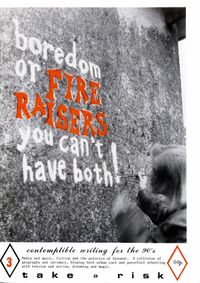

Fire Raisers – part four

Our journey into our magazine-publishing past concludes with The fire triangle, which is now live over at Alistair’s Unpopular. Incendiary comments positively welcomed!

The three printed issues of Fire Raisers can be downloaded in PDF format there or here:

In case you’re coming to the conversation late, here are the previous parts:

Boredom or Fire Raisers – part three

Here’s the third part of a series of four reflecting on Fire Raisers, the magazine that Alistair and I co-edited in the early nineties. The last part will be appearing over at Unpopular before long.

All three issues are available as PDFs via either of the links below or as paper copies for purchase. Do feel free to comment, whether as a contributor, a reader from back in the day, or on the basis of coming upon the magazines for the first time.

Daniel: Was it a pain having a co-editor? Would you have preferred absolute power?

Alistair: As a self-acknowledged control freak, I suppose I should answer yes to that. But actually no, it was fine. It was good to have someone else make some decisions about content etc, and of course your proof reading skills have always far outshone mine! Looking back though, I don’t actually remember how much real editing was needed. Did we turn down any contributions? Did we actually do any physical editing of other writers’ work?

I think the sense that we were properly collaborating was novel to us both, and exciting, and of course it never lasted long enough for serious issues to arise.

D: I think we took the ‘produced naturally’ approach to editing (analogous to groups recording without direction from an ‘auteur’ producer, leading to an end product whose audio quality is diminished but has greater charm). I’m sure that stemmed (a) from how sensitive we personally would have been at that time to editorial suggestion or interference, and (b) because we were a long way from having the skills you need to be an editor (some might say still are, if they’re wading through this!).

We did however turn down several proposed contributions, including one by a member of a certain pop group of whom we were fans. I meanly decreed in my mind that he should stick to music and leave the writing to us! I’ve always felt bad about that since.

But yes, I totally agree that the experience of working together on something was exciting – and instructive to two habitual loners like ourselves. Our chief obstacle as co-editors was of course one of us being in Scotland and the other in London in the days before email.

D: What reactions do you recall the magazine getting?

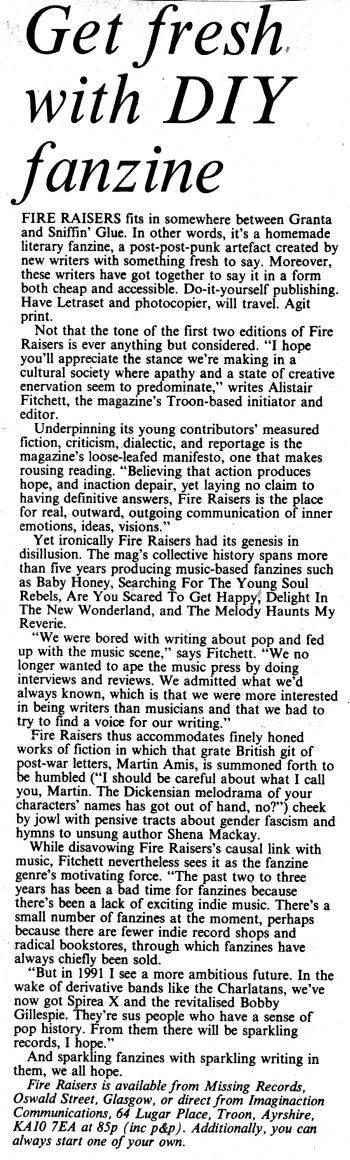

A: I don’t remember a huge amount, but then it was so long ago and many things have sunk into the depths of lost memories. I do recall the feedback from Richey, as noted previously. That would have been around the time of the Manic’s first Heavenly singles I think. I also remember doing a phone interview with David Belcher at the Glasgow Herald. Belcher was something of an iconic figure in the Scottish broadsheets at the time, championing lots of music and culture that the English broadsheets wouldn’t have touched with a bargepole. I sent him a copy of Fire Raisers on the off-chance he might like it, and then he phoned wanting to do a short feature. I’m sure I have the cutting somewhere in the vaults… The thing is, I remember thinking at the time that the article was a great coup and that it would surely increase sales. The truth was that it had an almost no impact at all. Except possibly to have the Scottish Library write to me and demand copies of all issues for their collection. They never paid, either.

Some years later, however, I sold a copy of my third Melody Haunts My Reverie fanzine to a bloke in The Cavern in Exeter. He came to be a good friend (even published my book of Pop witterings!) and it turned out he remembered buying copies of Fire Raisers at the local small press outlet and being impressed. So you know, people did take notice.

D: Having been tipped off by you, I made a special trip to King’s Cross early on the morning that particular edition of the Glasgow Herald was published to get hold of a copy – feeling somewhat like a playwright on the morning after press night, or Kerouac buying the New York papers the day On The Road was reviewed when I read: ‘Fire Raisers fits in somewhere between Granta and Sniffin’ Glue’!

That’s quite heartening, that Rupert had encountered Fire Raisers before he’d encountered you. It’s a perennial concern when you’re sending out writing into the world in no matter what form: are your words connecting with people and having an effect? Or are people completely disinterested? How can you know?

Being the hoarding type, I’ve kept a file of letters that first my fanzines and later Fire Raisers generated, and there are a fair few. There’s a great one from a Shaun Johnson of Melton Mowbray, who tried to get his local radical bookshop to stock the second or third issue of Fire Raisers only for them to refuse because ‘it didn’t sell well last time’! Shaun went on to say that Fire Raisers ‘is the best literary magazine on the market’, which may not be that far from the truth, given that the lifetime of literary magazines then as now tended to be brief, leaving plenty of windows where there wasn’t much or even any competition.

Other radical concerns were keener – a publication called the Exeter Flying Post got in touch to ask for ‘a statement of our aims’, which I presume I gave them.

And it was through Fire Raisers that we made contact with folk like Robin Tomens, who would later go on to write for Tangents. He bought the first issue in Rough Trade and wrote recognising Fire Raisers and his Ego were kindred spirits. Balancing up Richey’s verdict, Robin said he loved Carrie’s ‘Snowboots’ story, and Sam Matthew’s piece in the first issue. And that Fire Raisers was ‘beautifully produced’.

A: Although I would say it, I also liked Snowboots. Not sure what Carrie would think of it now, though perhaps she will let us know in the comments.

D: I think the tale of the beach shelter needs to be retold.

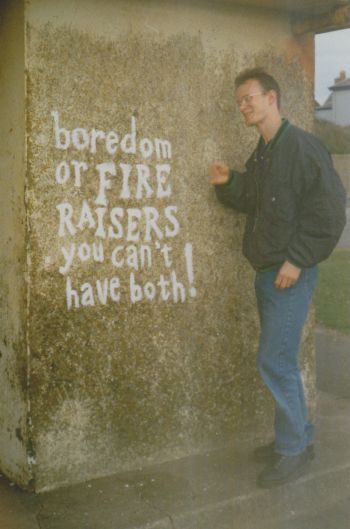

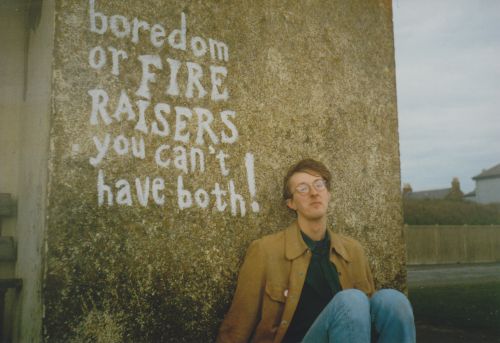

A: Oh gosh, the beach shelter… This was for the cover photo for FR 3, for which we wanted to borrow Paul Morley’s infamous ‘boredom or Fire Engines, you can’t have both’ line. I had this idea of painting the slogan (with ‘Raisers’ in place of ‘Engines’ of course!) on a beach shelter in my then hometown of Troon. I did the painting on the wall at around midnight after a night at my friend Stephen’s ‘Subculture’ club (I spent the night with a paintbrush and a small jar of white paint in my pocket) and then we went down the following day to take the photos. The cover star was a Subculture regular called Rozlyn, who I barely remember now. I think we asked her because she had a parka, though you can’t really tell that from the photo. There is also a photo from a few weeks later when you hitched up to Troon, I think. I’m standing beside my artwork, dressed in anorak and desert boots. Height of fashion.

The real interest in the story though is from several years later, when I had left Troon and was living in Devon. My mum mentioned on the phone that there had been a story on the front page of the local paper about an arson attack on a beach shelter in town. Seems the paper thought that the graffiti on what remained of the torched shelter (touched up just a few weeks earlier by our friends Andrea and Suzy) suggested that there were a group of arsonists at work in the town… naturally my mother was anxious about a visit from the local constabulary! I suspect the truth was that a bunch of glue-sniffing casuals got bored and cold on the front one night and decided to warm themselves.

The shelter was rebuilt, and these days the only graffiti you’ll find on it is of the ‘Baz 4 Shaz’ type. No imagination in the young people these days…

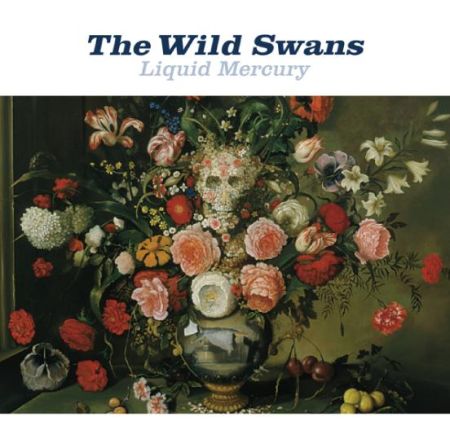

Liquid mercury

The Wild Swans’ unfinished business continues with a seven inch single and download, ‘Liquid mercury’ / ‘The wickedest man in the world’ (Occultation) and it sounds like the past is still preoccupying Paul Simpson. While neither track has the epic grandeur of ‘English electric lightning’, each is still bedecked with a rare degree of grace and great swoops of guitar – classic Scouse pop. And pop poetry, for ‘The wickedest man’ is another spoken word piece in the same gloriously melancholic vein as ‘The coldest winter for a hundred years’: ‘For me each year gets just a little tougher to get through / the regime just a little tighter / and the stars a little more distant’.

And, as I’m sure you’ll agree, another fabulous cover.

Fire Raisers – part two

Alistair has posted the second of our four-part reflection on Fire Raisers, in which we get our teeth stuck into taking risks, stylistic tics, and graphic design. Part one is here, and part three will appear on this blog next week. All three issues are available as PDFs or paper copies for purchase via either link. Do feel free to comment, whether as a contributor, a reader from back in the day, or on the basis of coming upon the magazines for the first time.

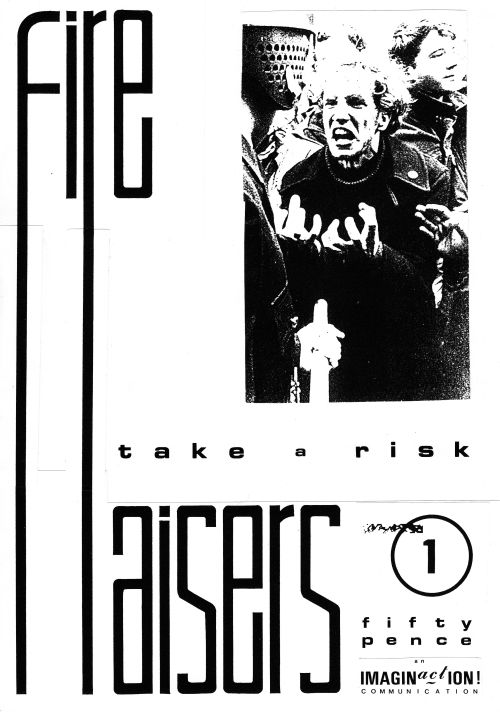

Fire Raisers – part one

About twenty years ago, having respectively produced a fair quantity of solo publications, Alistair Fitchett and I joined forces to co-edit a new magazine that for many and various reasons we stopped short of calling literary or cultural, though in truth it had aspirations to be both. In the first of four parts which will alternate across this blog and Alistair’s Unpopular, we discuss our motivations and the place in the world of such a magazine back then. We are making all three issues of Fire Raisers available in PDF format, so that you can make sense of the conversation, and perhaps enjoy the magazines in their own right.

We also have a few paper copies of each issue left; click here to purchase these perfect early Christmas presents for the literary fanzine fetishist in your life. Or for yourself, of course.

Oh, and if there do happen to be any Fire Raisers contributors or readers lurking out there, feel free to pitch in your comments as we go along.

- Fire Raisers 1 (PDF)

- Fire Raisers 2 (PDF)

- Fire Raisers 3 (PDF)

Daniel: Was the motivation behind Fire Raisers the same as that which led us to produce our solo fanzines? What do you think we were we aiming to achieve?

Alistair: After so many years it is difficult to recall exactly what motivations might have been driving me personally, yet I suspect they were very much the same as they were when making the solo fanzines in so much as they were about fulfilling a need to communicate and to share enthusiasms. Indeed that motivation is one that has been largely unaltered in what I’ve done myself since, with other solo fanzines, through Tangents and blogs etc. Having said that, I also concede that the motivation for Fire Raisers was probably subtly different, given that it was a shared idea. Perhaps we felt that Fire Raisers was a step up from the solo fanzines, a sense of getting a bit more serious and grown up about things. Certainly looking back at them now there is a sense of that, I think.

That said, I also think in many ways we didn’t raise our sights high enough, didn’t get anywhere serious enough. In retrospect that sense of refusing to compete in the traditional market place and staying resolutely underground held it back, I think. Looking back on the premise of Fire Raisers, I wonder if that had been a pitch for a more mainstream magazine with advertising and so on, it might have worked. Maybe not at the time, but certainly in the later ’90s and early noughties perhaps.

But then, that idea of being a ‘proper’ magazine was not really what we were trying to achieve anyway, so it seems a moot point. And actually it seems telling that we probably defined our aims in terms of what we DIDN’T want as opposed to what we did. And whilst the ‘manifesto’ editorial inserts still seem stirring and passionate, I’m not sure it’s exactly clear where those manifestos intended to lead. In short, I’m not sure we really had the slightest clue about what we intended to achieve! I’m not sure that we particularly cared either…

D: Yes, there was that sense of ‘Oh my god! We’re doing it… we’re fuckin’ doing it’, as the caption we used from a cartoon showing a subverted, rioting version of Tintin had it. It almost didn’t matter what exactly it was that we were doing. My hazy recollection is however that we were actually collectively quite sure about we thought the magazine should be, but I don’t think we were at that point quite able to articulate it with any great subtlety in print, especially when we tried to produce text co-operatively – to my mind it reads as a particularly contrived and diluted Alistair-Dan hybrid.

We were certainly totally clueless about marketing and selling the ‘concept’, as well as antagonistic towards the compromise inherent in giving over time and energy to those practices; it was all about the words and pictures, and putting them together. Still, each issue shows a marked progression in terms of making the magazine more accessible, at least in a superficial sense – the cover got more inviting with each outing. That came about partly because of the dressing down I got from the man in Compendium bookshop in Camden, who took it upon himself to critique the cover and contents in forensic detail one day when I dropped in to see how issue one was selling (not very well). I didn’t fancy that happening again so we took on board his suggestions!

Had we persisted beyond three issues – had desktop publishing been accessible to us then; had I not disappeared off to France – I think the penny might have dropped, and we would have tried to put the magazine on a more professional footing. The notion that it was a step up from our solo efforts suggests that too.

A: Ah, isn’t hindsight a wonderful thing? Really though it’s impossible to consider those ‘what ifs’ and ‘maybes’ isn’t it? Because the needs that drove you to France, and the impending (or eventual) arrival of affordable publishing technologies were very real and, one could argue, equally undeniable. Our collective fiercely held opinions on commercialisation and almost OCD level obsession with not ‘selling out’ would also have inevitably hampered much forward movement for some time too, I fear. Not that that’s a bad thing necessarily, but nevertheless I think it would have been a very real barrier to making progress in terms of creating a product with much of a potential audience.

Interestingly I met with an old colleague from Art school the other week. We had not seen each other in twenty years, but he told me that he sometimes uses my old fanzine experiences as an analogy in business coaching situations. It all hinges on that sense of micro-conflicts between otherwise apparently similar people, or at least people with similar interests and roles. So that whilst as a fanzine writer I might have been arguing openly and heatedly with another fanzine writer about, say, which Talulah Gosh single is the best, to an observer it appears an illogical source of conflict. To the outsider it seems like, ‘hey, both these people love this group I’ve never heard of! Why don’t they use that shared love to make something great happen?’ So the micro-conflicts are damaging and holding back potential growth or positive development. Of course you can argue that those very micro-conflicts are at the heart of obsessive pop-cultural consumption, and that they are indeed desirable in that media and age context, which means that maybe the analogy doesn’t cross-contextual boundaries. Nevertheless I think it’s very useful, and I think helps to explain why I don’t think Fire Raisers could have grown beyond what it was within the context it found itself.

D: I was party back then to more micro-conflicts than I care to think about! Politics is of course also largely about micro-conflicts, with the same resulting positives and negatives.

D: Who or what were our inspirations, and our enemies?

A: I’m struggling to think of inspirations. Didn’t we think we were very much out on a limb, doing something different? I like to think so. And I like to think that we were fairly true to that. Certainly there were lots of dire small press fanzines that were doing fiction and other such things, but were they mixing it up like we intended? I’m not sure. Certainly I suspect things like Debris were a reference point, and to some extent people like i-D and The Face perhaps, at least in terms of those publications’ original ethos. Though by the time of Fire Raisers i-D and The Face were probably seen as much as enemies as anything else. I think perhaps the idea of the ’60s underground press was a reference point. IT and such like. Also, I would guess the more politically minded situationist publications were in your mind Daniel?

But yes, there was a lot of importance put on the idea of enemies in those days, wasn’t there? I am not sure if that was a reflection of the age, or of ours. I am not sure if people of that age now feel the same sense of having to take sides, of being for this and against that. I suspect in reality things are not much different and that the percentage of any given generation that really cares about such things at a given age remains roughly the same. But as for who our enemies were? Is ‘everyone else’ too flippant an answer? Perhaps so, and yet it feels honest and indicative of our glorious naiveté.

D: Oh yes, I don’t think it was until a while after the ashes of Fire Raisers had cooled that I finally got myself out of that situationist straitjacket. It was an unfortunate part of the baggage that stopped us from trying to sell or market the magazine. Situationism’s critique of capitalism was so devastating, and its political aspirations so remote, that for a long time I felt bleakly trapped by it. That came out in what I wrote for Fire Raisers. Having Guy Debord and Mark Eitzel as chief inspirations is not a great combination if you’re after producing happy text, or for that matter, a happy bunny writing it.

The fact that we felt unable to name more than a couple of even vaguely like-minded enterprises in the first issue – both in any case the projects of people who contributed or went on to contribute to the magazine – suggests that what you say is right. We did feel out on a limb. Debris was great, but it was more properly journalistic in its approach than we ever envisaged being. I never really bought into The Face and i-D thing, though later, when I lived in Bristol and started going to clubs , I bought them out of curiosity (and a lack of anything else to go for) in terms of that culture.

I think I was hoping to elicit from you particular individuals who inspired us as well as publications, whether that was personally or in a literary sense. As well as Debord and Eitzel, I was big on Georges Perec at the time; an excellent stylistic corrective to all the Kerouac I’d read. And personally Ross Reid (Cornish fanzine writer and sports journalist) was also a huge inspiration for me – in fact (now it can be told) he was the subject of ‘Spike’, the opening article in issue one. In February 1990 – in a classic example of micro-conflict! – he sent out a circular called ‘Anger the angels’ to certain friends and two of the Esurient groups with one of the classic photos from the May ’68 riots on the front, telling us all to ‘wake up!’ and issuing me with an injunction about getting on with Fire Raisers: ‘don’t fiddle with matchsticks while you can/could blowtorch the fucking lot.’ He demanded – alongside what I now see is an isolated and ever-so-slightly paranoid plea for contact – that we think big. We tried.

And of course we should direct a nod of appreciation in Max Frisch’s direction, for it was his play’s title that we appropriated for the magazine. Likewise a nod to Fiona of our Devonian contingent of friends (and contributors), who originally passed it our way. I haven’t reread the play since, but what I recall is a blend of Brecht, anarchism and something more conservative, the end result being not dissimilar to the recent German film The Edukators.

Anyone else you would add to the list?

A: Well, as you were perhaps moving on from the Kerouac obsession, perhaps I was moving into it. Hence the large photo of the man himself accompanying my new Orleans missive. I think there was something of the stream of consciousness prose in the Big Flame extracts too, although that was tempered with some conscious stylistic editing too. I suspect my Sylvia Plath obsession came slightly later…

Like you, I had never particularly bought into the i-D magazine culture, although as an Art student perhaps I was more inclined to dabble. Certainly I had loved The Face since the early ‘80s, and Blitz (which was run partly by Paul Morley, yes?) was a regular on my desk, although by the time of around ’86 into ’87 I’d had my head turned by things that would shortly coagulate into the dreaded ‘indie’ style, and this was very much seen to be in opposition to the glossy ‘style’ magazines.

I always thought it was funny that several of the images that were in my first (handwritten!) fanzine Delight In The New Wonderland were from fashion spreads in The Face. And I liked that the image we used to accompany the ‘Helsinki’ piece in Fire Raisers 3 about clubs came from i-D.

D: Was there a place in the world at the time for the kind of magazine we were aiming to produce? Is there one now?

A: This is something I’ve thought about often over the years, not specifically in reference to Fire Raisers, but in general. And I must admit that it is with something of a resigned sigh when I conclude that no, there isn’t and no, there wasn’t. Not if one wanted to make a living out of it at least.

I think if you drew a Venn diagram of potential markets for the things that ‘we’ like(d), then you are left with a tiny area that, globally, may never amount to any more than a few thousand people. Which in real terms is less than negligible. Our disinterest in pretty much anything remotely approaching ‘mainstream’ (or that our interest in anything remotely mainstream is placed in unfamiliar contexts) also precludes the potential marketplace for anything we might produce.

That’s not a criticism though, and nor is it a reason for not doing something. It’s just an observation and an acknowledgement.

D: I suppose it depends upon how much ground we might have conceded to the mainstream, or, to put it less grudgingly, how hard we might have worked to bring what we liked in a cultural sense to a readership that might be less familiar with it. Certainly we were never going to make a living from the magazine itself, but it might have led more directly to the chance of making a living from freelancing. But we were actively engaged in the enrichment of our own cultural lives, if no-one else’s. A salary, food and a roof were never going to be enough, with all due admission that we were and are lucky enough to be living in a time and place when we can say that.

If the cultural blend had been suitably varied – and I think it was well on the way to becoming so – we might have generated interest in and – to use your analogy – shaded a fair number of those intersections at the centre of that Venn diagram. If the way the internet has evolved proves anything, it’s that there are an almost infinite number of overlapping or interlinked musical and cultural localities; in our own small way, with our contributors’ collection of varied interests, we anticipated this – and contributed to that evolution itself when it began to happen.

A: There’s a symbiotic relationship, isn’t there, between our understanding of those cultural connections and the media through which we exploit the links. So without the possibilities offered by the Internet, for example, would our sense of connectedness be lessened? Or increased? Does the physical size of those distributed networks impact on that? So for example, is there any less a sense of belonging to a group when the membership is measured in the millions as opposed to the hundreds? And how ‘real’ is the sense of belonging? And how do you measure or judge the ‘reality’ anyway?

Sorry, that’s a lot of questions and thoughts starting to get up their own arses, but I do think it’s interesting. And I don’t think that Fire Raisers could have increased its audience without changing its fundamental form. Which ties in to what we were saying about contexts.

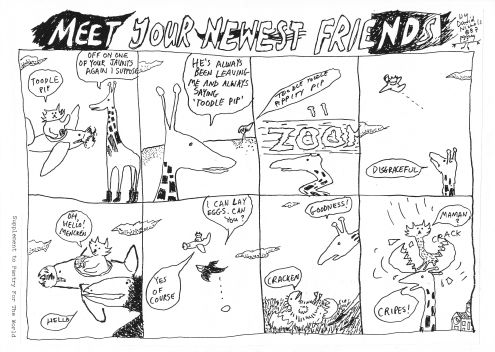

Meet your newest friends

Bringing – at last – this whole exercise of republishing my solo fanzines to a close, here is the cartoon supplement for Pantry For The World, where we once again enter a portal on floor 7½ of the Mertin Flemmer Building in Melbourne and emerge into the mind of David Nichols circa twenty years ago.

David’s work from the previous issues of my fanzine can be seen here.

If anyone would care for Pantry For The World in unexpurgated PDF form, you can help yourself below; the advantage being that you don’t have to squint as much as you may have been doing at the jpegs I’ve been posting. Thanks for sticking with it.

Next up – Fire Raisers.

- Pantry For The World fanzine, 1989 (best quality – but 23mb)

- Pantry For The World fanzine, 1989 (smaller file size version – 2mb)

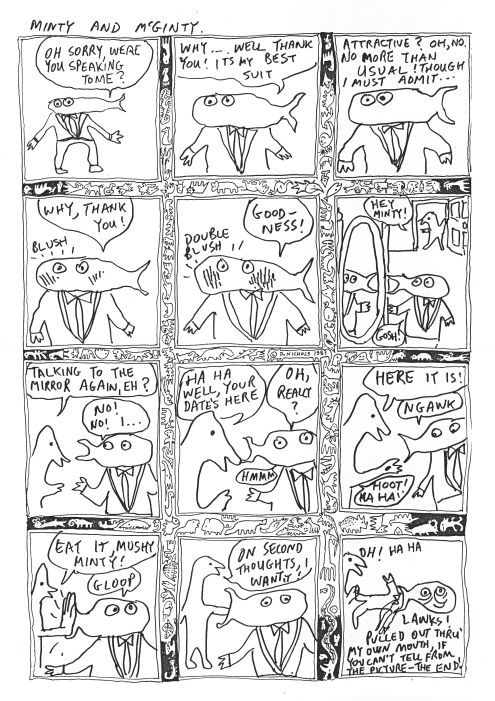

Minty and McGinty

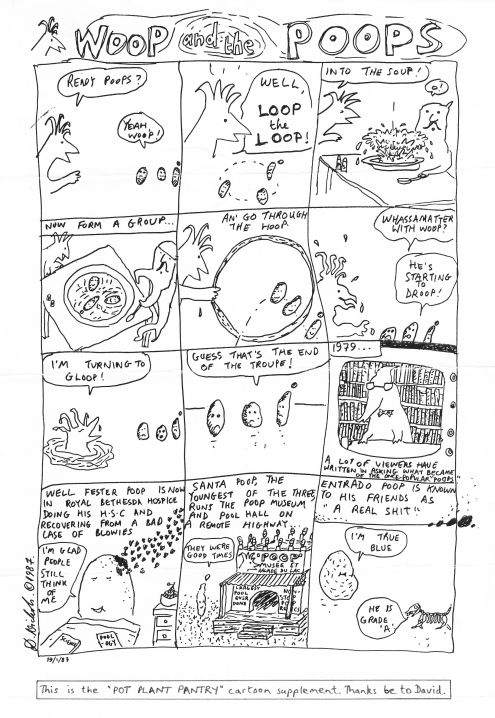

The cartoon supplement for Pot Plant Pantry was once again given over to the surreal lunacy of David Nichols’ creations.

To my (admittedly warped) mind, Minty and McGinty anticipates the wonderful Mo Willems’ Elephant & Piggie and Pigeon series of books for children.

And Dr. Seuss meets Viz in the form of Woop and the Poops, with a bit of Cambridge Footlights satire thrown in for good measure.

Woop and the Poops is dedicated to Tim, for remembering it down the course of twenty years.

David’s work from the previous issues of my fanzine can be seen here.

Paper covered editions

I’ve been enjoying Littlepixel’s ongoing and eclectic series of album covers turned into Pelican books. They recall Andy Royston’s Faber-esque ‘paper covered edition’ sleeve for McCarthy’s ‘The well of loneliness’. Thanks to Bimble, you can compare and contrast that cover with the Pelicans – and download the still rousing five song 12 inch while you’re there.

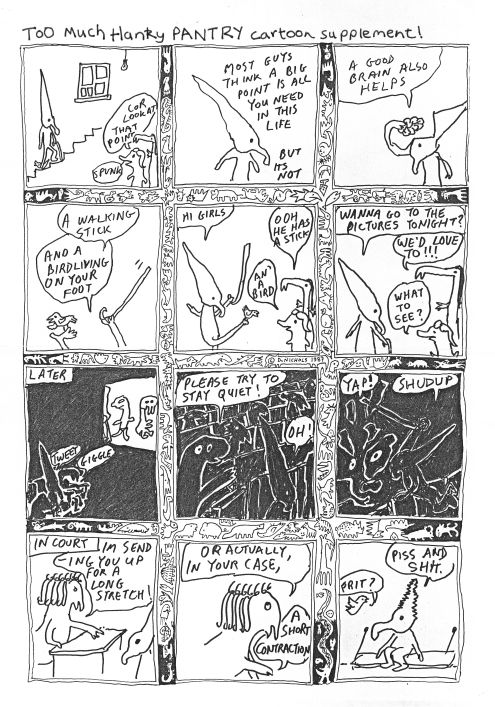

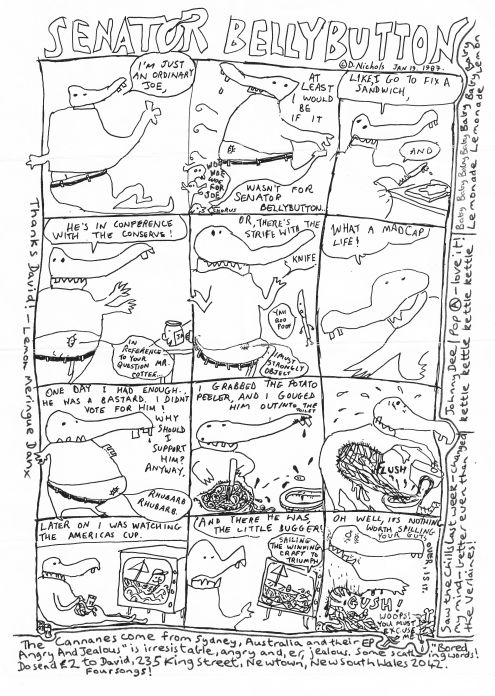

Senator Bellybutton

My small innovation for issue two of the Pantry fanzine was – in minimalist imitation of the weekend papers – to include a supplement; the space allowed David Nichols to do the honours once again on the cartoon front.

David now blogs at Lorraine Crescent, and in one of those moments of synchronicity that the internet’s exponential growth makes more or less inevitable, he has just posted a piece about the comics he read as a boy, reflecting on the effect their ‘silliness’ had on him: ‘I took it all in, the bald dads and food obsessions and angry policemen, and made it work for me as a way of seeing.’

David’s cartoon’s from the first issue are here.

Chance meetings

This really should have been a Tangents article.

A couple of years ago, Tangents would have been for several reasons the perfect forum in which to rave about Rachel Cohen’s A chance meeting: intertwined lives of American writers and artists (Vintage). The book explores the moments or points at which pairs or trios of artists’ and writers’ lives intersected or gently touched against each other and in so doing it becomes a celebration of literature, art, photography, and cinema, as well as of the common ideas connecting their forms and the lives of their makers. Then there is the felicity – almost certainly unknown on the author’s part – of its echo of (the group) Josef K’s finest moment, and its probably known and knowing nod to a Brief encounter-esque sense of romance; for Rachel Cohen’s book is as much about what is left unsaid as about what history records as having been said. Its acceptance and understanding that writers come in all shapes and sizes, that some write of a life of adventure in snatched moments between one escapade or assignation and the next, and others form adventure from a solitary life of sedentary reflection, is the literary equivalent of the stuff in which Tangents dealt over its ten year history.

In truth, beyond the shared title, there’s not much to link Rachel Cohen’s A chance meeting with Josef K’s ‘Chance meeting’, other than the somewhat deliberate circumstance of individual taste, and the suggestive nature of the song’s lyric, reprising the tone of David Lean’s film and Noel Coward’s screenplay:

‘The red sky behind you

The feeling you’ve been here before

You lived in the past dear

With things we all gave up then

I met you again there

But this time it weren’t for real’

But connections spark and snake in all directions as you read, inevitably going beyond the ones that Cohen herself makes, or gently presents without comment, like Willa Cather meeting Flaubert’s niece, and writing up the encounter in an essay called “A chance meeting”, or the title of the novel written by one of her subjects, W.D. Howells, A chance acquaintance. Mention of Joseph Cornell will necessarily stir the attention of any fan of the Clientele’s music. The story Cohen tells is this:

In 1943, Joseph Cornell wrote to Marianne Moore to thank her for some small amount of praise for a collage of his illustrating a story in an arts magazine. The salutation was held up by an armadillo, armoured animals exerting a fascination for Moore displayed in her poetry, and Cornell wrote that her words were ‘the only concrete reaction I’ve had so far, and they satisfy and affect me profoundly.’ Cornell was voicing the gratitude that a deliberately lonely artist starved of reaction suffers through long years of obscurity. His inclination was to fall in love with anyone who paid him attention, all the more so because it was someone he admired. It led to an exchange of gently romantic letters, and to a meeting, though whether strictly speaking you could call it a chance one is debateable. Of the meeting itself nothing can be said but that Moore saw Cornell’s basement workshop and his boxes-in-progress. But Rachel Cohen gives us the tenor of their almost exclusively epistolary relationship and describes presents Cornell sent by post (a valentine of worm-work paper and an ancient book of rare animals), treading softly through the facts to offer from inside each story telling perspectives such as her notion that ‘people very often sent things to Marianne Moore in the hopes of getting back the language with which to talk about them, almost as if they were sending specimens to a zoological expert in order to find out the precise genus and Latin name.’

Along with three dozen other such encounters between writers, artists, photographers, thinkers, critics (and Charlie Chaplin), the book also narrates the second and third meetings between Cornell and Marcel Duchamp, which rested on Duchamp answering a phone call by chance. Duchamp gives Cornell a present, perfect in its symbolism: ‘He had picked up a red-and-yellow glue carton that said “strength” on one side and, admiring the American phrase, had written “gimme” above it and then signed the whole “Marcel Duchamp,” dated Christmas 1942.’

Cohen’s book is full of such anecdotal gifts, but it is also strong on the way art forms and their purveyors rub off on (and up against) each other, and on the artistic urge which drives their creations, their lives, their relationships with the people to whom they are drawn and the ones from whom they retreat. With its contextualised counsel from one writer or artist to another, it becomes a creative primer, and a caution against the wasting away of talent.

Carefully chosen photographs inform the text. Richard Avedon’s 1960 picture of John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg and dancer Merce Cunningham is terrific; the laughing trio look like a particularly joyful early 1980s New York indie band. Cohen’s description of the daguerreotype of Henry James Senior and Junior – ‘disturbing in the ghostly aliveness of its subjects’ – also stands for her own book. She makes what must have been painstaking research seem effortless, stitching it into the whole so that you barely notice the thread binding the material together, and all without a footnote in sight. There is empathy with all of her subjects, but not always sympathy – for example, she has little time for the shellac vanity of Katherine Anne Porter.

Neither does she make more of the connections than there is. Beyond the intrinsic pleasure she presents readers, she concentrates on her essential job, which is to make them want to go away and read the books of those of whom they were previously unaware; in my case William Dean Howells and Sarah Orne Jewett, the lesser known works of Mark Twain and Willa Cather, and maybe even Ulysses S. Grant’s memoirs. But she still allows me to draw the line at Gertrude Stein, and set me imagining the context of meetings that happened between artists of my own cultural acquaintance. I’ve often wondered whether – as well as serve coffee to Thomas Mann when working in a dining hall – the young Jack Kerouac really did pass Thomas Wolfe on Brooklyn Bridge in a ‘raging blizzard’, as he reports in Vanity of Duluoz, and whether Wolfe might have taken the young football star for a drink if Kerouac had mustered the courage to speak to him.

In White bicycles: making music in the 1960s Joe Boyd writes of playing Nick Drake to John Cale, and of the amazed and excited Cale going round to see the young singer there and then, a seemingly improbable meeting of the confident Welshman and the diffident Englishman which the very next day resulted in the recording of ‘Northern sky’ and ‘Fly’. The fleshed-out story behind an easily missed credit on the sleeve of Bryter later.

These connections, both real in terms of lives touching each other, and imagined, in the sense of the artistic repercussions of such encounters, are made of much the same stuff that informs A chance meeting. And any regular readers of Tangents who have ventured into these obscure parts are guaranteed to enjoy it as much as I did. Or your money back.

Sonic comics

The second contributed page to Lemon Meringue Pantry, split in two. The cartoonist is David Nichols, who produced comics and a fanzine called Distant Violins. The comic that came my way was Soon, featuring strips such as ‘Pebbles of the dead’ and ‘The day the world caught fire’; David’s extraterrestrial humour emboldened me to ask for more of the same for my fanzine. He also drummed – or rather percussed – for the Cannanes, whose Bored, angry and jealous EP was released the following year (1987). Its rough acoustics and heavy dose of sarcasm in the form of ‘You’re so groovy’ bear up well after all these years. They’re still going, albeit without David, who went on to write and then revise a history of the Go-Betweens (Verse Chorus Press, 2003), a book which in giving an affectionate but not reverential account of the group very much does them justice.

David’s humour – at least as it stood twenty years ago – comes from a not dissimilar well to that drawn upon by Nicholas Gurewitch for the Perry Bible Fellowship. The execution, of course, is different, with David offering something akin to the early Cannanes’ sound – rough, ready and spontaneous – while Gurewitch varies his style and colouring to suit his absurdist ideas, more often than not finessing them to perfection.

Art And Anti-Art

The two pages by other contributors were easily the best thing about Lemon Meringue Pantry. Here is the first of them – a masterpiece of provocative politico-aesthetics by Chris Jones, who under the pseudonym Tintin was editor of Bullfrog fanzine. At the point I met him he had recently come up with the AAAA tag. If you crane your neck and squint carefully, you’ll see from the scan that AAAA’s merchandising arm was Jesus – The Products. I still have a piece of toast in a nicely labelled Jesus – The Products bag which Chris sold me at a later exhibition of what could loosely be described as his work. Chris was one of the influences moving me to become increasingly politically active, and it was largely through him that I got into the situationists – a more culturally satisfying route than via Malcolm McLaren. Debord and Vaneigem made a lot of sense to me in those days, with theory and proposed practice that turned the world upside-down and inside out, but the demands an involved reading of them placed on the human psyche were cult-like in their intolerability. What do I think of them now? I would need the prompts provided by a re-reading The society of the spectacle and The revolution of everyday life to tell you that.

Chris later made music with groups called the Gore Vidals, Use and Pre-dog, put out creative writing in a publication called Fast Hard and reinvented himself as X-Chris before I lost touch with him. Having often wondered what he might be up to in a world whose virtual or online versions has to some extent caught up with the kind of approach he espoused, I did battle with everyone’s search engine of choice and eventually found video footage of him in among the background material for the Tate’s displays marking the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade. Chris argues – as I half-suspected and hoped he might still be doing – that resistance is not futile. (He’s at 3:16, sandwiched between Mike Phillips and Mark Wallinger.)